Farmers raise alarm over polluted water flowing in from Canada

Farmers raise alarm over polluted water flowing in from Canada

Water flowing into the U.S. has abnormally high levels of fecal bacteria. Locals near the U.S.-Canada border say more needs to be done to protect people, salmon and shellfish.

LYNDEN, Wash. - Concerns along the U.S.-Canada border are being raised about fecal contamination flowing into Washington State.

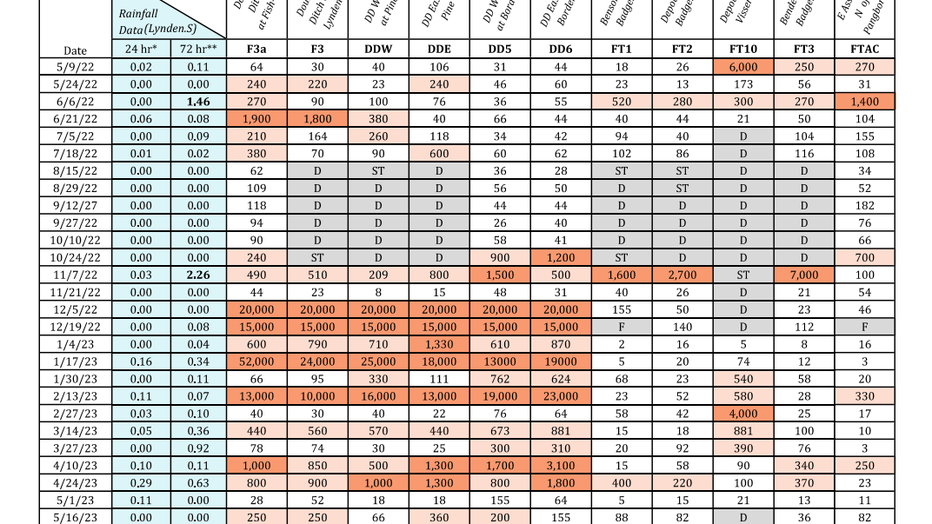

Over the past several months, a concerning amount of fecal contamination has appeared, as bi-weekly testing in Whatcom County has continually turned back levels hundreds of times beyond the allowable limit.

Water quality tests along these sample sites aim to have samples containing less than 100 fecal coliform/100mL. In recent months, the numbers have reached as high as 52,000 fecal coliform/100mL along Double Ditch.

"We’re right on the border," said Fred Likkel, the executive director of Whatcom Family Farmers—pointing to parallel roads, which represent the border on a remote stretch of road near Double Ditch Stream. "There’s no other answer than it’s coming directly from Canada."

The stream Likkel is standing alongside is one of five main drainages that originate in Bristish Columbia and flow into Washington, all draining into the Nooksack River and eventually downstream to Portage Bay and the Lummi Nation’s primary shellfish growing areas.

The concerns range from accessible water along the border, salmon, recreational use in Lynden all the way to the shellfish farms that are important both economically and culturally to local tribes.

Water quality was a concern for many years in Whatcom County. Fecal bacteria levels got high enough that tribal shellfish beds were shut down over health concerns.

"When we talk about shellfish beds, we’re talking about the proverbial canary in the coal mine," said Christine Woodward, the Portage Bay Shellfish Advisory Committee chair.

Woodward spent decades sampling water along in Western Washington. According to Woodward, more attention needs to be directed at the troubling numbers that are coming out of Whatcom County.

"Do you live downstream? Do you use water—do your children? Are you concerned about their health? If so, you need to be worried that water in our community is unsafe," said Woodward.

Not long ago, levels recorded in Whatcom County would lead to direct contact between Washington State and their counterparts across the border.

The BC-WA Nooksack River Transboundary Technical Collaboration Group worked together between 2018-2021 to track down non-regulated pollution. Those efforts lost steam during COVID-19, and Canada changed how it handled testing, reducing efforts to sampling at a handful of locations just five times a month.

According to a spokesperson with Washington State Department of Agriculture, Canada no longer has staff that coordinate with Washington-based programs that could respond when high levels of fecal bacterial are found.

Earlier this month, farmers with Whatcom Family Farmers directed a letter to Governor Inslee and his counterpart in B.C. asking for a meeting with key leaders to determine steps that could lead to improved water quality.

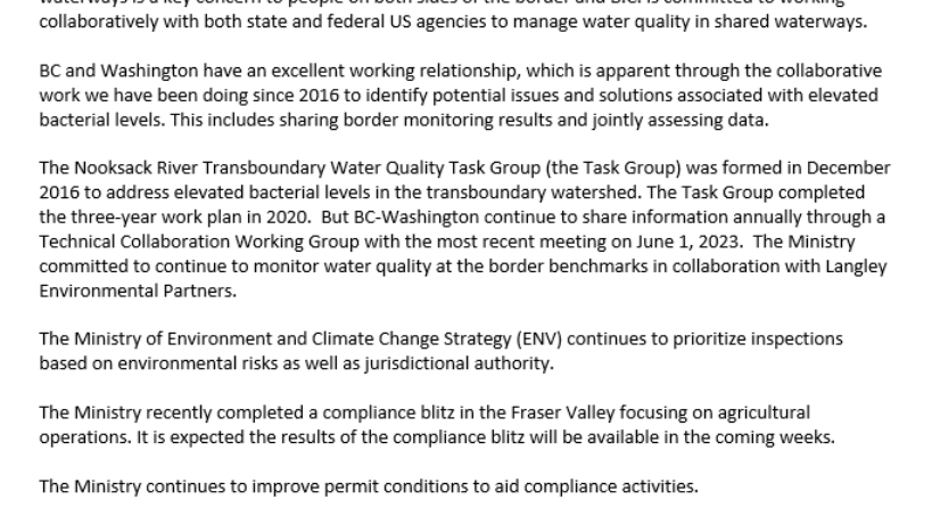

British Columbia's Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy told FOX 13 that they have a shared interest when it comes to local watersheds.

In a written statement, without addressing a change in how they interact with American counterparts, they wrote that they’re prioritizing inspections, adding that they recently wrapped up a "compliance blitz" with results expected to be published in the coming weeks.

In part, it reads, "The province, through the ministry will continue to provide the resources necessary to carry on this important work."

Full statement from BC Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy

On the American side of the border, farmers are wary of any promises for improvements in the future.

"Government-speak says we’ll discuss it in a year," said Larry DeHaan, a veteran dairy farmer and owner of Storm Haaven Farm. "We’ll discuss it, then we’ll get to it, and maybe next year we’ll have a solution to the problem. That’s what I’ve heard for 40 years or more."

DeHaan, like many farmers, have grown frustrated by slow movement. DeHaan lived through major changes and compliance efforts when shellfish beds were initially shutdown.

Standing alongside one of the creeks that recently saw a spike in fecal bacteria; he listed agencies ranging from EPA to various Washington State agencies that watched farmers very closely as the industry made changes to ensure rivers, streams and creeks were safer.

Now, DeHaan is growing concerned that the solutions are outside their hands. That after years of watching work be done on this side of the border to improve water quality, things are out of control with no concrete answers.

On top of the concerns over pollution, his creek has run dry in recent summers—a shock, given local efforts to ensure salmon survive. A few weeks ago, the Bertrand Creek ran dry and salmon were dried up near his property. He can’t say whether those issues stem from Canada, but he said without better communication, it’s hard to figure anything out.

"We have fish dying from a lack of water," he said. "That’s an international problem when the water is supposed to come across an international boundary."

Governor Inslee’s office told FOX 13 that they are aware of the concerns, and a pair of letters that were recently sent; one by Whatcom Family Farmers, another by Whatcom Clean Water Program, a partnership of local, state and federal agencies that work together in the region.

A spokesperson said that the Governor’s office is reaching out to the people who wrote the letters to schedule a meeting.

The concern for those living in Whatcom County is that it could be too late. Water testing taken near shellfish beds are viewed on a rolling 30-month calendar, meaning if water from creeks and streams don’t dilute before making it down the Nooksack and out to shellfish beds a single high reading could cause months, or even a year-long closure.

RELATED: Himalayan glaciers could lose 80% of their volume if global warming isn't controlled: study

Get breaking news alerts in the FREE FOX 13 Seattle app. Download for Apple iOS or Android. And sign up for BREAKING NEWS emails delivered straight to your inbox.

"We need this to be a collaborative effort," said Woodward. "We cannot do this by ourselves; we have to have Canada help us."