Southern Resident Killer Whale research shows unique bond between mothers, sons

Photos of J Pod calfs taken under Federal Permits: NMFS PERMIT: 21238/ DFO SARA 388 (Mark Malleson/Center for Whale Research)

FRIDAY HARBOR, Wash. - Researchers studying the Southern Resident killer whales have found that female orcas protect their sons – but not their daughters – from fights with other whales in their post-menopause years.

The findings – published today in the journal of Current Biology – suggest that female killer whales have evolved to pass on their genes by helping their male offspring.

Orcas, along with humans, are one of the few species known to experience menopause. This discovery unlocks additional questions about what role menopause plays in changing how female orcas interact with their sons, and why support is directed at sons and not daughters.

A team consisting of researchers from University of Exeter, University of York and the Center for Whale Research were able to discover the benefit for male orcas through studying "tooth rake marks."

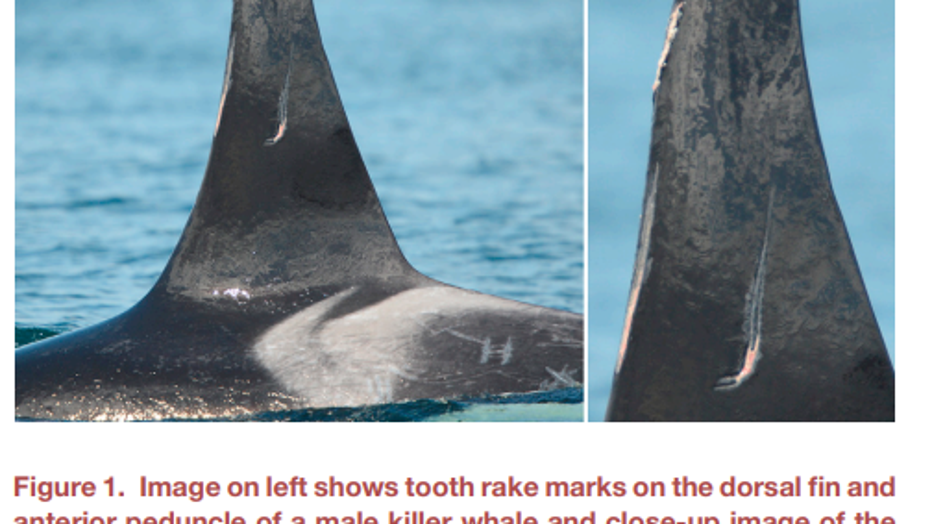

Photos from the Center for Whale Research shows tooth rake marks on a male killer whale.

Rake marks are a type of scarring left behind when a whale scrapes its teeth across another marine mammal, male orcas were found to have fewer marks whenever a mother was present that had stopped breeding.

"We were fascinated to find this specific benefit for males with their post-reproductive mother," said Charli Grimes, the lead author from the Centre of Research in Animal Behaviour at University of Exeter.

"We can’t say for sure why this changes after menopause, but one possibility is that ceasing breeding frees up time and energy for mothers to protect their sons."

Orcas live in close-knit groups, and are considered a matriarchal society. Female orcas lead groupings known as pods.

Among the more interesting findings by the team, is that while female orcas tend to protect male orcas later in life – they specifically protect their own male offspring, not their grand-offspring – or any other whales within their social unit that isn’t a direct-male offspring.

Darren Croft said it can’t be said for sure, why mothers protect their sons – but noted that older females could be using their experience to help sons navigate social encounters.

"They will have previous experience of individuals in other pods and knowledge of their behavior," said Croft, "and could therefore lead their sons away from potentially dangerous interactions."

"Just as in humans, it seems that older female whales play a vital role in their societies – using their knowledge and experience to provide benefits including finding food and resolving conflicts."