Stillaguamish Tribe begins massive restoration plan for neglected salmon habitat

Restoration planned for the Stillaguamish River

A few years back the Stillaguamish Tribe purchased hundreds of acres along the Stillaguamish River. They're attempting to restore the habitat to its original state.

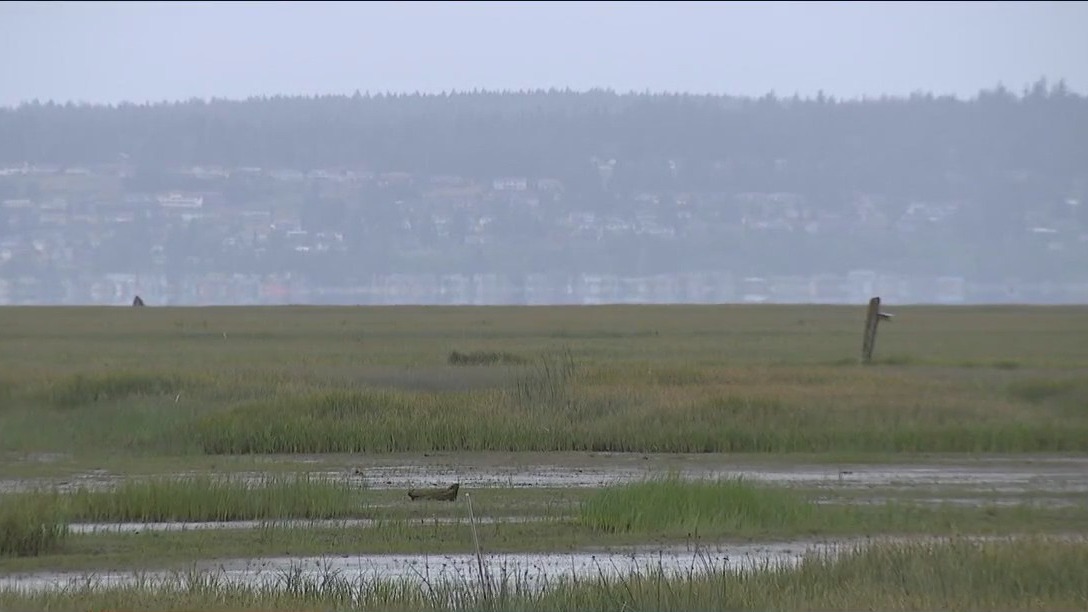

STANWOOD, Wash. - As Kadi Bizyayeva walks a large berm overlooking Port Susan in Stanwood, it is hard to overlook the importance of the land beneath her feet.

Bizyayeva, a Stillaguamish Tribal Councilmember, explains this land underwent major changes more than 100 years ago.

In the 1800s, settlers built dikes and levees to hold back the Stillaguamish River. It created fertile farmland, but also eliminated habitat that served as a nursery for juvenile salmon.

"We are now one of the limiting stocks," explained Bizyayeva. "Our fish populations are constraining fisheries across the entire West Coast."

Members of the tribe have not lived off commercial fishing for years. However, the ability to fish remains culturally important.

"It was a huge part of religion," said Bizyayeva.

A few years back, the Stillaguamish Tribe purchased hundreds of acres along the Stillaguamish River. They re-named it zis a ba, a name that would traditionally have been passed down from generation to generation. In this case, it’s being placed on the land.

The Stillaguamish Tribe is attempting to restore the habitat to its original state. A $12 million plan has been projected that will include removing two miles worth of levees, removing buildings on the land and building floodgates in a new location.

NOAA providing funding to help with Stillaguamish restoration projects

NOAA announced $3.31 billion worth of investments this month for work across the country. A large portion of that money is heading to Washington for coastal resilience, salmon recovery and infrastructure.

It’s believed that restoring the land will help the Chinook salmon population returning to the Stillaguamish River, a species on life support in the Whidbey Basin—an area that consists of three of Puget Sound’s most important salmon-producing rivers: Skagit River, Snohomish River and the Stillaguamish River.

"We’ve lost upwards of 80% of our estuaries in the Stillaguamish," explained Charlotte Scofield, a tribal fisheries biologist. "We’re really lacking habitat. It takes a lot of time, a lot of work and a lot of collaboration."

In this case, the zis a ba restoration is one of 23 projects in the Whidbey Basin receiving money from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

NOAA announced $3.31 billion worth of investments this month for work across the country. A large portion of that money is heading to Washington for coastal resilience, salmon recovery and infrastructure.

"We’ve been able to do habitat restoration for years," said Laurel Jennings, a habitat resource specialist with NOAA. "This is our area of expertise, however, it’s not been at this dollar amount before. The dollars are so much more in magnitude than what we’ve funded in the past we know this is an opportune time to do big work and advance projects we haven’t been able to do before."

NOAA’s funding is passing through the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, and into nine lead organizations doing work throughout the area.

While the work is important for salmon recovery, the benefits will be long-lasting beyond species local governments are trying to rescue.

In the short-term, efforts to revive a keystone species is important. Long-term, WDFW tells FOX 13 that the work will have an impact on climate resiliency. As sea level rises coastal communities are under greater threat of flooding, including infrastructure that people utilize.

Returning the zis a ba property to its natural "norm," takes pressure off the area.

"We’ve put a lot of hard infrastructure in place that are at-risk," said Jay Krientiz, an estuary and salmon restoration program manager. "That puts people at-risk and our transportation infrastructure at-risk. We’ve changed the landscape over the last 100 years a lot, and those places need room for the rivers and the tidewaters to move around."

The work, however, won’t happen overnight. The funding through NOAA is used for specific parts of the project—it won’t fund the entire project, but it will help fund pre-project monitoring, design, permits and more.

"It takes a community to do this work on a watershed scale," said Krientiz.

However, the proof that it can work is already within reach. Adjacent to the zis a ba project, a separate estuary project is roughly a decade underway. The Nature Conservancy has already returned a similar, albeit smaller, chunk of land to estuary habitat.

It’s proof that while humans can degrade habitat quickly, we can also restore it over time.

Bizyayeva told FOX 13 that the work is decades in the making, her ancestors brought these ideas to a point—her and the rest of the tribal council are moving those plans along.

She explained it’s an exciting time to be involved in this project, especially given that so few large-scale sites exist that can be returned to nature.

RELATED: PHOTOS: Whale watchers spot a deer swimming alongside an orca near San Juan Island

Get breaking news alerts in the FREE FOX 13 Seattle app. Download for Apple iOS or Android. And sign up for BREAKING NEWS emails delivered straight to your inbox.

"As soon as we restore this we’re able to utilize it," she said. "Our local farmers provide an important economic component to this state. We like to say we’re farming a different type of crop. One that will provide some climate resiliency, better infrastructure and some historic and traditional components too."