The push to preserve Black culture in Seattle's Central District

The push to preserve Black culture in Seattle`s Central District

The push to preserve Black culture in Seattle`s Central District

SEATTLE -- While protesters for the Black Lives Matter movement occupy several blocks in Capitol Hill outside Seattle Police Department's East Precinct, some Black community groups are a mile away, pushing to preserve their culture in Seattle's historic Black hub.

The Central District is where Seattle's Black community thrived. On 23rd Avenue and East Union Street, Black businesses like Earl's Cuts and Styles were staples for decades.

"I started cutting hair in this area in the late '80s," Earl Lancaster said. "It was a thriving Black community, businesses, restaurants, clubs."

Lancaster opened his own shop in 1992. But over time, that community he spoke of tapered off.

"People come in from out of town, they come here and say, 'I heard this is a Black community, where's Africatown?' They don't see it," he said.

In the Central District, development turned to displacement. The once-vibrant intersection where Lancaster had his barbershop became unrecognizable to the families who called it home.

"What I'm seeing now, to be honest, it really makes me sad," said TraeAnna Holiday, who grew up in the CD and is now a community organizer for Africatown Community Land Trust.

The CD became a haven for Black families by design and racial discrimination.

"They pushed us into this area because they didn't want us anywhere else," Holiday said.

In the 20th century, Seattle neighborhoods had covenants to keep out Black people. Where they and other minorities were allowed to live and own, the city redlined the area, a signal to banks not to loan money there.

That policy and others created significant barriers for Black families to buy homes, start businesses and prosper.

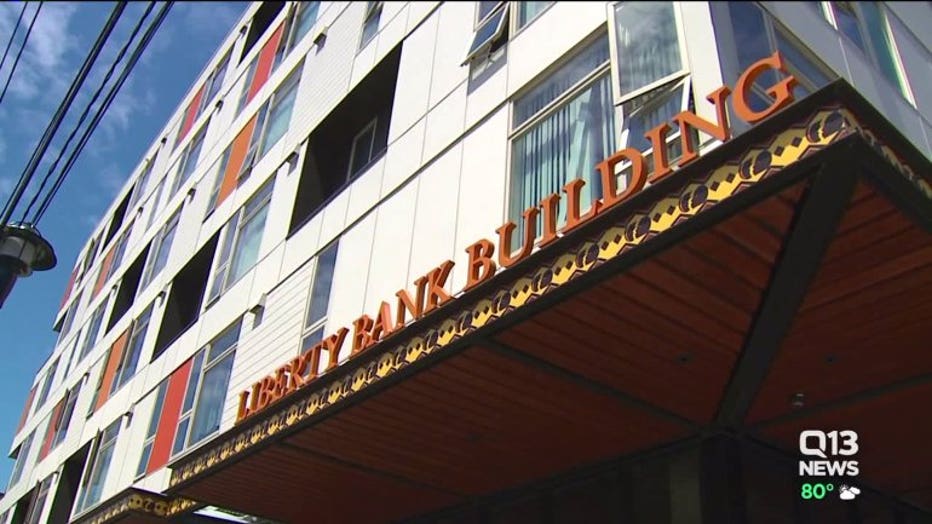

The CD pulled up its own. The first Black-owned bank in the Pacific Northwest was on 24th Avenue and East Union Street. Liberty Bank lent to Black families when white-owned banks wouldn't.

That corner continues to be a lifeline for a culture that is quickly disappearing in the Central District.

"They pushed us here and then they pushed us out so we really have to now push ourselves back in," Holiday said.

When KeyBank, who owned the old Liberty Bank, was ready to sell, they offered it to Capitol Hill Housing below market value to turn the land into an affordable-housing space. The developer worked with community groups like Africatown Community Land Trust to see Liberty Bank Building come to fruition.

Today, the building is a nod to the Central District's culture and accessibility, with 115 affordable housing units on top and on the bottom, Earl's Cuts and Styles and more Black-owned businesses coming soon.

"I'm grateful to still be here," Lancaster said.

Across the street where his barbershop used to be, more new development is hammering away. Like the street corners around it, old establishments, like Ms. Helen's, are now a memory.

" didn't even think, well, what was here before? How can we bring some of that vibrancy or culture back to our development, back to our project?" Holiday said.

Looking around 23rd and Union now, the intersection looks like any other in the city.

"Seattle needs to remember the history, recognize the history, acknowledge the history that Black people and others from the global majority were pushed into certain situations," Holiday said.

Now, they're pushing back. Liberty Bank Building was just a start. The next project is Africatown Plaza at Midtown.

After Lake Union Partners bought Midtown Center, which used to house Central District establishments like Earl's, Africatown Community Land Trust, Capitol Hill Housing and Forterra secured 20 percent of the block for a project similar to Liberty Bank Building. Lake Union Partners will develop the other 80 percent.

For Holiday, whose own family was pushed out to Federal Way, it's just the beginning.

"We need 30 Liberty Bank Buildings to bring all of our displaced people back," she said.