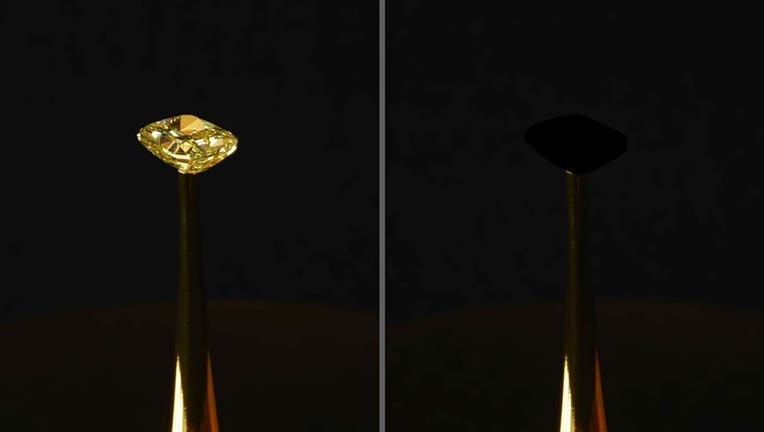

There's a new 'blackest black' material, and it can cloak even this bright, sparkling diamond

MIT engineers have created a material that is 10 times blacker than anything else ever been reported, the school announced. (Diemut Strebe/MIT)

MIT engineers have created a material that is 10 times blacker than anything else ever been reported, the school announced.

The material is made from vertically aligned carbon nanotubes, or CNTs, which are microscopic filaments of carbon. (Think a fuzzy forest of tiny trees.) The team grew them on a surface of chlorine-etched aluminum foil.

The foil captures at least 99.995 percent of any incoming light. This means the material reflected 10 times less light than all other superblack materials, including Vantablack that previously claimed the title as the world's "blackest black."

Researchers published their findings in the journal "ACS-Applied Materials and Interfaces" last week.

This new material can obscure anything, no matter what angle it's viewed from. So if a diamond were covered in it, its rigid features would be invisible.

People can see the cloak-like material for themselves as part of "The Redemption of Vanity," a new exhibit at the New York Stock Exchange.

The artwork features a 16.78-carat natural yellow diamond from LJ West Diamonds that is estimated to be worth $2 million. The team coated the diamond with the ultrablack material, making the typically brilliantly-faceted gem appear as a flat, black void.

The art project was conceived by Diemut Strebe, an artist-in-residence at MIT in collaboration with Brian Wardle, an MIT professor of aeronautics and astronautics, and his team.

"The unification of extreme opposites in one object and the particular aesthetic features of the CNTs caught my imagination for this art project," Strebe said in a statement.

Wardle said the material can have use aside from its artistic value.

"There are optical and space science applications for very black materials, and of course, artists have been interested in black, going back well before the Renaissance," Wardle said in a statement.

A coincidental surprise

Wardle and his co-author of the paper Kehang Cui, a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, weren't trying to create an ultrablack material. They were experimenting ways to grow carbon nanotubes on electrically conducting materials, such as aluminum, to boost their thermal and electrical properties.

"Our group does not usually focus on optical properties of materials, but this work was going on at the same time as our art-science collaborations with Diemut, so art influenced science in this case," Wardle said.

Wardle and Cui have applied for a patent on the technology. For now, they are making the new CNT process freely available to any artist to use for a noncommercial art project.

While their CNT material holds the record, Ward said the blackest black is a constantly moving target.

"Someone will find a blacker material," he said, "and eventually we'll understand all the underlying mechanisms, and will be able to properly engineer the ultimate black."