Plans to restore grizzly bears in Washington has people drawing a line in the sand

Bringing back grizzly bears

Scientists have been working to import species, and in other cases, usher in the natural migration of species, for the past several decades to restore the full spectrum of animals that once roamed Washington state.

SEATTLE - The intent to introduce grizzlies back into the wild of the Pacific Northwest has communities split.

Depending on who you are, imagining a grizzly bear roaming the North Cascades can spur thoughts of a gentle giant or a monster foaming at the mouth. To scientists, the idea of a grizzly returning to Washington state is less hyperbole, and more about completing an ecosystem that humans tore apart decades ago.

"It’s an incredible opportunity," said Robert Long, the Woodland Park Zoo’s director of the Living Northwest Conservation Program. "It really comes on the heels and completes something we’ve seen in the North Cascades for the past two decades—that is, the grizzly bear will be the last large mammal species missing from our landscape."

Scientists have been working to import species, and in other cases, usher in the natural migration of species, for the past several decades to restore the full spectrum of animals that once roamed Washington state.

That work has included wolverines, Canada lynx, wolves and fishers. Restoring species that historically existed in our area is meant to restore natural processes.

FILE-A large grizzly bear is spotted in Yellowstone National Park. (William Campbell/Corbis via Getty Images)

As Long explained, we don’t always know the full impact a species can have on an ecosystem until we see it in play. That said, we know that inland grizzlies have a diet that largely consists of root vegetables, plants and bugs.

"They really rototill big areas," said Long. "So they serve to keep meadow systems open. They consume huge amounts of berries and plant foods, which serves to distribute seeds across the landscape."

The hope to restore a grizzly population goes beyond Washington State, though. Grizzlies were listed as a threatened species in the lower 48 states in 1975, leading to restoration in places like Yellowstone. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Parks Service has spent decades looking at locations to restore bear populations.

Past efforts have been planned, but ultimately failed to come to fruition.

THE CONCERN

Introducing a species isn’t without concerns. While scientists have spent decades discussing grizzly re-introduction strategy for the North Cascades ecosystem, there’s similarly been efforts to stop them.

As far back as the early 90s, recovery plans were drafted to re-introduce grizzlies to Washington. No plans have made it to the finish line, with the Department of the Interior abruptly ending a previously approved plan in 2020.

In the previous process, the support was strong for grizzly restoration. But, that support included people from throughout the U.S.

When you look closer at the in-state comments, the support dropped as you got closer to the areas where re-introduction is considered.

"We believe if you come and see what we’re really dealing with, you’ll find this is not the right time," said Pam Lewison, the agriculture policy research director for Washington Policy Center.

"I think the biggest concern really comes back to: ‘Why us? Why now? Why not somewhere else?’"

While grizzly re-introduction would allow Washington to regain a historic species, the location overlaps with the efforts to recover wolf populations. Wolves have already become a concern thanks to attacks on sheep and cattle, rankling ranchers.

Wolves have also been blamed for reducing elk populations, which in turn can harm big game hunters.

As Lewison explained, an increase in predators will only exacerbate issues in communities that settled into their livelihoods long after apex predators had been removed.

"You don’t have to have a predator—whether it’s a wolf, a cougar, or a grizzly—right next to your livestock for it to impact an animal," said Lewison. "They know that that predator is out there. What it does is causes spontaneous abortion of calves, it causes cattle to not get pregnant again, it causes extremely low birth rate. It causes the animals themselves to lose weight due to stress."

Lewison isn’t the only one sounding that alarm. Representatives Dan Newhouse and Cathy McMorris-Rodgers have sent letters to both U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the National Park Services requesting additional time for locals to review plans.

Rep. Newhouse has also filed a bill in Congress that would effectively kill the current efforts to re-introduce grizzlies.

AN ARGUMENT FOR A RETURN

Grizzly bears roamed Washington state for thousands of years prior to their disappearance.

Experts say that biodiversity is key to maintaining the overall health and stability of an ecosystem. In the simplest terms, the elimination of grizzly bears in our region have changed the landscape we live in.

Prior to human involvement, grizzlies were an apex predator that brought balance to the food chain; not only through prey, but in terms of spreading plants.

Since inland grizzlies have a hefty diet of root vegetables, plants and bugs, they tend to spread seeds throughout a region. In doing so, they have an impact not only on prey animals, but the wildlife throughout their range.

That impact began to disappear quickly in the 1800s. Documents from the Hudson’s Bay Company show that in a 25-year period, more than 3,000 bear pelts were shipped out of local forts. As furs gained value, bear populations dropped.

Few grizzly bears have been spotted in modern history in the Cascades.

In 1967, a hunter shot and killed a grizzly bear in Washington State for the last time. In the years that followed, grizzlies were seen so sparingly people began calling them "ghost bears."

Over the past two decades, a handful of sightings were disproven. The last confirmed report of a grizzly in the North Cascades was in 1996.

As Long explains, returning grizzlies to the landscape would make the Pacific Northwest one of the few places anywhere in the U.S. with an intact assemblage of large mammals.

"It’s an optimistic story, and we hope people will recognize that," said Long. "There’s been this recognition that we need to actively be recovering bears here, and we are now as close as we’ve ever been to that happening. It’s really an amazing opportunity to right some of the wrongs that humans have done to large species like grizzly bears."

ONGOING EFFORTS TO RE-INTRODUCE GRIZZLY BEARS

Public meetings are taking place this week in Newhalem, Darrington and Winthrop to give Washington residents a chance to learn more about the current draft plan, and proposed rules for grizzly introduction.

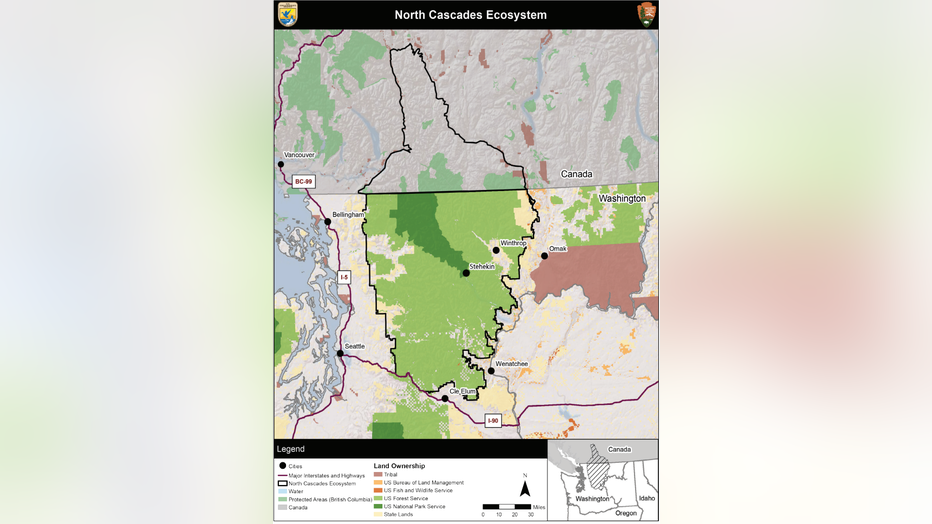

The current "preferred plan" involves making the North Cascade grizzlies an experimental population, also known as a 10(j) designation.

That essentially means that a species will be released into a suitable habitat outside the species’ current range, but within its historical range.

Grizzlies would be trapped from neighboring regions with inland bear populations. The plan would focus on younger female bears, with the goal of moving three to seven grizzlies a year for 5–10 years. The goal is to reach a population of 25 grizzlies that can be managed, with a long-term hope of 200 grizzlies in the area within 60–100 years.

Researchers note: "We would expect the number of grizzly bear depredations (attacks on livestock) to be low while the population of bears is small. However, depredation could increase as the population grow."

If the grizzly bear population were to reach the expected 200 bears, a Department of the Interior formula projects three livestock depredations a year, including two sheep and one cow.

The efforts to re-introduce grizzly bears has been an ongoing effort since the 1970s. In 1975, the grizzly bear was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Grizzly bears currently occupy roughly 2% of their former range. Conservation Northwest has estimated that the number would double if every recovery zone in the U.S. across four states were enacted—meaning grizzly bears would remain extirpated [removed] from more than 95% of their historic range.

Scott Schuyler, the policy representative for the Upper Skagit Tribe, which is within the recovery zone, has publicly applauded efforts to return the grizzly to its historic range.

"The grizzly has profound cultural significance and its restoration will enrich our ancestral lands and help restore the foundations of our cultural practices," said Schuyler following the announcement that work was underway to reintroduce grizzlies once again.

GRIZZLY BEAR ATTACKS

While the argument surrounding grizzlies often revolves around cultural, economic and ecological impacts, it’s worth noting that any discussion of grizzly bears being introduced to a large swath of land will involve concerns of bear attacks.

The possibility of bear attacks on humans has spurred plenty of public comments in the latest go-around.

"Both science and history demonstrate that is reasonably foreseeable to anticipate that a [grizzly bear] may attack, injure, or even kill a park unit visitor, employee, or contractor," one respondent wrote.

Thousands of similar notes have been sent in, and while bear attacks are rare, people will argue over what the word "rare" means.

"When you look at the data, ‘rare’ with wolf attacks means there is virtually no data," said Lewison. "You can look at records from other states with wolf packs and you’ll find almost nothing about people being attacked by wolves. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, but it’s extraordinarily rare."

"When you look at the data for bear attacks on people, it exists," she remarked. "You can find that data."

Nature recently crunched the numbers and estimated that 11.4 attacks occur in North America every year.

One of the most recent attacks occurred in Canada at the Banff National park – the Calgary Herald reported that the final message from a couple read: "Bear attack bad."

The two veteran backpackers, known for exploring nature, became victims of a rare deadly bear attack. In fact, the couple had bear spray, per park officials.

Those in favor of a re-introduction of grizzly bears are quick to point out that grizzlies and humans co-existed for hundreds of years. The Upper Skagit Tribe stated that pre-contact, their tribe co-existed with grizzlies for 10,000 years.

"There’s very few actual incidents where grizzly bears and humans come into conflict," said Long. "It’s very unfortunate when it happens, and it does happen, but it’s very infrequent and for the most part, grizzly bears and humans co-exist and can live on the same landscape."

For more information about upcoming meetings, and links to send in your own public comment on the proposal to re-introduce grizzly bears to Washington state, you can click here. The comment period is already open and runs until Nov. 13.