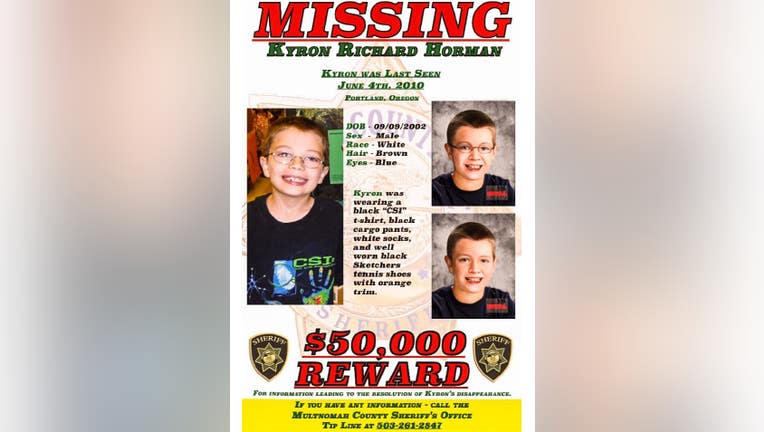

Kyron Horman's mom 5 years after son's disappearance: 'It doesn't get easier with time'

PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — It's said that time heals all wounds. For Desiree Young, it's not worked out that way.

The pain she first felt five years ago when her son Kyron disappeared from Skyline School in Portland hasn't softened. If anything, her emotions are more ragged today, she said. Tears flow often. The gnawing hole inside hasn't filled, not even a little.

"It doesn't get easier with time," Young told The Oregonian. "I still wake up crying and praying, hoping today will be the day."

Young tries to keep busy. She's a budget analyst at Southern Oregon University. She goes to therapy. She counsels families as coordinator for Team Hope, a group of parent volunteers for the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Young addresses at least one conference every year that's sponsored by the center. She also has shared her perspective as a parent of a missing child at nationwide law enforcement conferences, including for the Amber Alert system and Child Abduction Response Team Training under the U.S. Department of Justice.

CART teams are made up of professionals from various disciplines, including counseling, education and search and rescue. When a child goes missing, they work together, something that doesn't always come naturally to independent agencies.

Young, who lives in Medford, played a role in Southern Oregon's CART certification a year ago.

Her public engagements are part of her drive to help improve the response when children go missing, she said. They also help her navigate her own rough times.

"There's part of that that gets me through every day," Young said. "It's different than talking to a parent of a missing child. It gives you a different focus. It provides a little bit more of a feeling that I'm doing something to improve the future."

But Young bounces between despair and hope like a yoyo. She worries about straining her personal relationships, knowing that people can reach a point of saturation where they don't want hear again about the sorrow. She's still married to Tony Young, a major crimes detective with the Medford Police Department. Their relationship remains rock solid, she said.

"We made a pact," Young said. "We weren't going to give up on Quinn, my oldest son. We weren't going to give up on each other. And we weren't going to give up on Kyron."

After Kyron disappeared, Young piled up presents, cards and stuffed animals in the room that Quinn, now 20, shared with Kyron when he stayed with Young.

But Quinn became uncomfortable sleeping in a shrine, he told his mother. So she tucked much of it away, keeping a few key items, like the teddy bears and a stuffed alligator from Quinn, on Kyron's bed.

A plastic Crystal Geyser water bottle, the last that Kyron used, is still in the refrigerator with his initial on the cap. The photos and drawings on the door haven't changed either since he disappeared. Young wants to keep those reminders of her son.

She buys him presents on his birthday and at Christmas. They are always for a child of 7, the age when he disappeared. She can't imagine him older.

On Thursday, the June 4 anniversary date, she plans to be at the Wall of Hope, a cyclone fence decorated in honor of Kyron in a grassy area outside the Xtreme Edge Gym in Beaverton where Young's ex-husband and Kyron's father, Kaine Horman, works out every day.

In September, Young is planning another search.

She hopes to bring in 15 tracking and cadaver dog teams from Washington, Idaho, California and Florida to search in the Portland area, but wouldn't say where. She's organized several other searches in the past.

She said they've turned up evidence implicating Terri Moulton Horman, who was married to Kaine Horman at the time Kyron went missing. Terri Horman took the boy to a science fair before class at Skyline School and then walked him to his classroom before leaving.

"We've found evidence to suggest that Terri might have been trying to get rid of things connected to Kyron," Young said, referring to the previous searches. "She's not going to talk until we have evidence to confront her. We have to find it."

Terri Horman and her lawyers have said she wasn't the last person to see Kyron that day, but haven't offered further explanation. She has never faced charges.

Young said she's coordinating the search with the Multnomah County Sheriff's Office, but said the agency wouldn't take part. She plans to keep searching until every inch of territory is covered.

"There are so many different areas that have to be searched thoroughly," Young said. "It's a big canvas. There is no way that law enforcement can do that."