Washington sailor's body returns home decades after his death

WA sailor's body returns home decades after his death

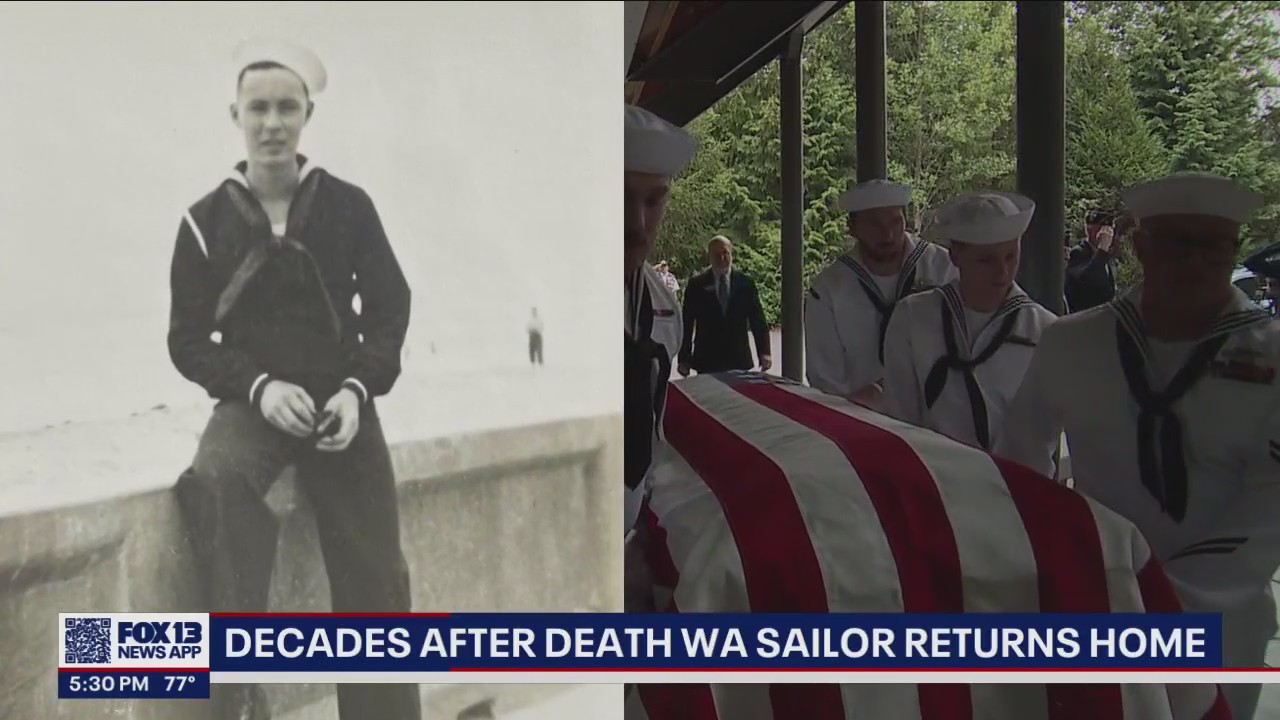

It took more than 80 years, but Radioman Third Class Frank Hoag received his long-awaited welcome home at Tahoma National Cemetery in Kent.

KENT, Wash. - It took more than 80 years, but Radioman Third Class Frank Hoag received his long-awaited welcome home at Tahoma National Cemetery in Kent.

Hoag, who was killed during the attack on Pearl Harbor, was among the hundreds of service members recently identified by naval scientists using DNA testing. His remains were among the last sailors identified, thanks to his family.

"I don’t give up," said Nancy Melary with a laugh.

Melary’s mother had talked about wanting closure surrounding Hoag’s death for decades. Sadly, she died a little more than a year before the mystery was solved.

Through a program dubbed The USS Oklahoma Project, scientists with the Defense Department and the University of Nebraska have identified more than 90% of the 394 remains that were recovered from the USS Oklahoma and were "unknowns" when the project began.

In fact, Hoag’s remains were among the few that were not identified.

Melary was notified shortly before the plans for an 80th anniversary memorial that Hoag’s remains had not yet been identified, and that they’d be buried in a mass tomb, similar to the one that was dug up after a push to identify sailors and give closure to families.

Previously, Melary had written the U.S. Navy to get Hoag’s records. She’d traveled to look at hard copies of genealogy records, but by 2021, genealogy records were readily available online. She launched her own hunt for relatives and found one person—several generations removed and living in Canada—that was a descendant of the same paternal lineage.

That individual and his DNA sample, painted a picture for researchers and unlocked the mystery of which remains were those of Hoag. Previous DNA samples, linked to maternal lineage, were too similar to other soldiers to eliminate other matches.

And the mysteries didn’t stop there, even on the day of the burial; Melary learned that Hoag had arrived in Hawaii only one day before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The single photo she’s had of him shows him on a beach, meaning her lone keepsake of her long-lost relative was taken one day before his death.

"I’m just happy he’s home," she said. "I’m very, very happy he’s home. It’s been a long journey."

The ceremony was small. Melary was joined by her husband, a few veterans, and the men and women who work at the National Cemetery to ensure that no veteran’s memory is lost.

Melary told FOX 13 News she was blown away by the people she saw, while noting it was hard to be so far removed from his death, that no other family was on-hand.

Though Hoag wasn’t surrounded by cousins, brothers, sister and friends, in the end, Melary said she was certain his parents were looking down from above, proud that he’d made his journey home to Washington State.

Radioman Third Class Hoag was a graduate of Aberdeen High School. He joined the U.S. Navy voluntarily at a pivotal time in American history. He, along with 428 crew members, died in the early morning of Dec. 7, 1941.

Within minutes of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the USS Oklahoma had capsized, trapping hundreds of sailors who were below-deck in their racks.

Hoag was awarded a Purple Heart posthumously.

It took more than 80 years, but Hoag made it home.