Seahawks star Kenny Easley gets real about long, painful road to forgiving team

SEATTLE-- Former Seahawks safety and Hall of Famer Kenny Easley sued the Seahawks decades ago. Today, he's still not sure if he should have settled that lawsuit.

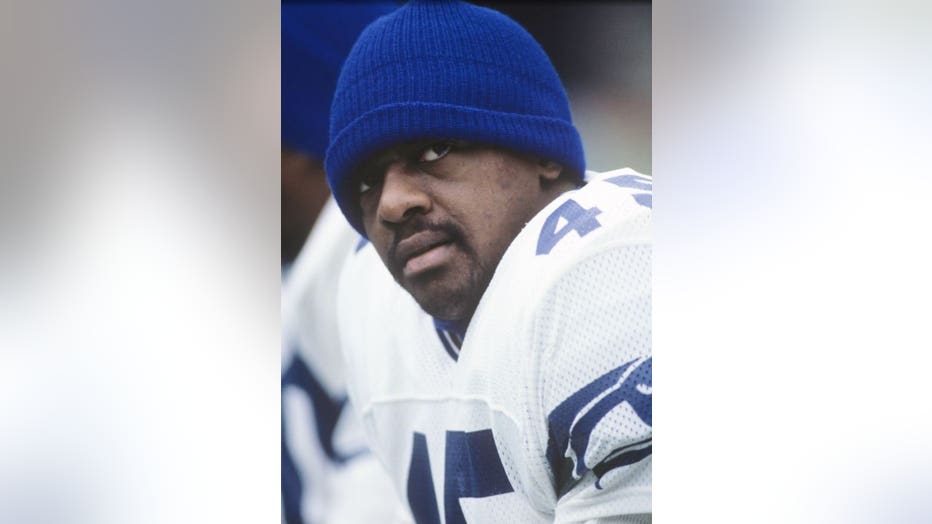

With that said, the Seahawks retired Easley's jersey No. 45 last Sunday, making him the fourth player in team history to receive the honor. The No. 12 is also retired. It belongs to the Seahawks' fans.

It comes 30 years after kidney failure forced Easley from the game.

“I came into this league as the best free safety in college football. Bar none,” Easley said during an interview with Q13 News.

In his voice you hear the fire that fueled him on the field decades ago.

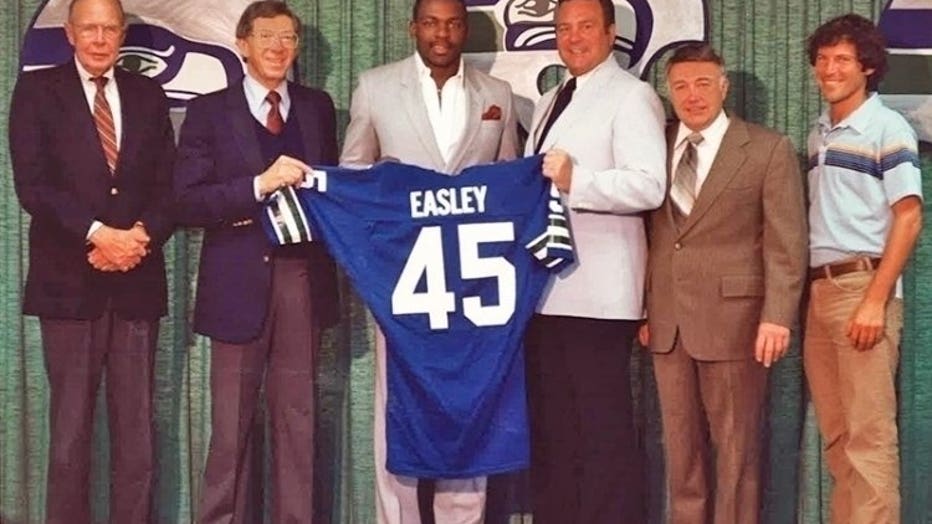

The Seahawks selected Easley, a three-time consensus All-American at UCLA, with the No. 4 overall pick in 1981. Easley never worked out for the Seahawks. He didn't think the team would draft him, and he admits, he didn't want to play for a relatively new franchise in Seattle.

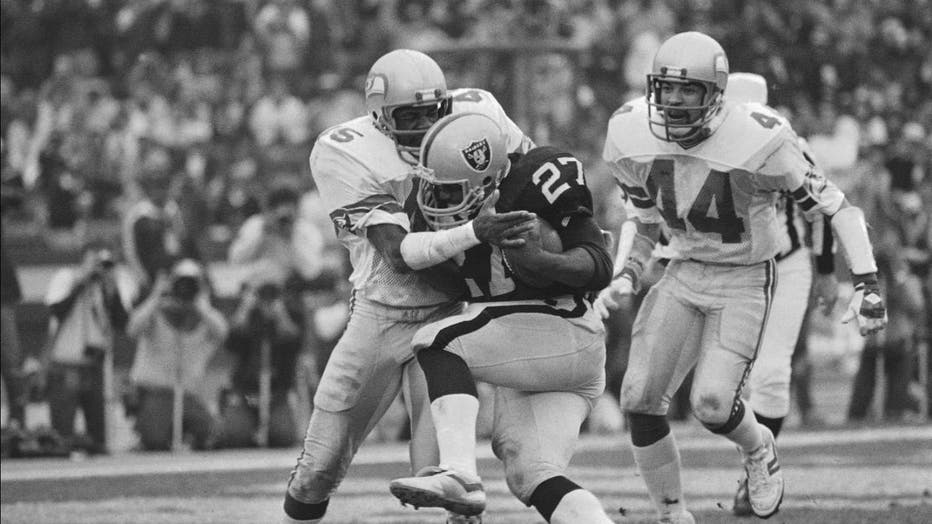

Easley made the most of it, becoming known for devastating hits and dazzling interceptions.

The honors rolled in:

Defensive rookie of the year in 1981. Defensive player of the year in 1984. Selected to the Pro Bowl five times.

But during year seven, those bruising hits that always hurt others started hurting him.

“Just like that, it’s over with,” Easley said.

He was told his kidneys were failing, forcing him out of football for good.

Easley explains, “I wanted to play 15 years. I don’t know if would have gotten to 15 years playing the way I played, but I certainly should have played more than 7 years.”

Easley blamed the team, claiming they gave him handfuls of ibuprofen to relieve pain, unknowingly destroying his kidneys and leading to several kidney transplants.

“As a 28-year-old guy who lost his career because of a bad decision that the organization made, I wanted to fight,” he said.

So he sued the Seahawks, and says court records revealed team doctors and the general manager knew his kidneys were failing but didn’t alert him or pull him out of the game.

“The Seahawks, for whatever reason, made the decision to put me on the field," he says.

"They never told you?" I ask.

"Never told me,” he answers.

Easley settled the lawsuit, but was so bitter, he completely turned away from the game he once loved. He says, “I didn’t watch football for 15 years. I didn’t watch college. I didn’t watch high school. I didn’t watch pro. For 15 years. That was the only way.”

Until 2002, under new owner Paul Allen, the Seahawks reached out to Easley, asking him to join the Ring of Honor in the team’s stadium and reconcile their differences, something Easley’s wife Gail pushed him to do.

“When it was time for me to make the right decision, I was lucky enough to have a good woman that told me to do it," Easley says. "Because i could have probably held out another 15 years.”

He’s returned to Seattle again years later to raise the 12th man flag, connecting with the coaches, other former and current players, and the fans.

Then just one year after having triple bypass surgery, Easley was inducted this past August into the NFL Hall of Fame, football’s most exclusive club.

His proud wife and three children were right there in the front row to celebrate the magical moment.

CANTON, OH - AUGUST 05: Kenny Easley poses with his bust during the Pro Football Hall of Fame Enshrinement Ceremony at Tom Benson Hall of Fame Stadium on August 5, 2017 in Canton, Ohio. (Photo by Joe Robbins/Getty Images)

His son, Kendrick Easley, says of his father, “He’s been a role model for me, since forever, since I was young. I’ve always looked up to him and I’m very happy and proud of him.”

Daughter Giordanna, who works for the Los Angeles Rams in communications, chimes in, “It really just shows the journey of life, how you have barriers, or you have obstacles, but you can always overcome them.”

Of being inducted into the Hall of Fame, Kenny Easley says, “To me it’s amazing, because I don’t know many people 30 years after they’ve done what they’ve done have gotten an award like that.”

One bust of the player inducted ends up in the Hall of Fame itself. A copy is given to the player.

On Saturday, September 30, Easley loaned his to the Northwest African American Museum in Seattle to be displayed for the next several months.

“There’s a season for everything, and apparently this was my season.”

A season of accomplishment, gratitude, and with his former team, forgiveness.

“When given lemons, you make lemonade. You make the best lemonade you can make and that’s what I did. That’s the lesson in this.”